As we know the English Language has gone through a vigorous transformation, down the ages. After the Anglo-Saxon period or the Old English period the most, eventual and significant era was the Middle English period. Middle English, starts its journey in the history of English Literature, after the migration of the Germanic tribes the Anglo Saxon, when the Normans invaded England, in 1066 and continued till the renaissance, somewhere around 1558.

This span of more than 500 years is divided into three parts

i) Before Chaucer (1066-1300)

ii) Age of Chaucer (1300-1400)

iii) Age of Revival (1400-1500)

In this article, we are going to know about the literature and the literary works, before and after Chaucer.

Eventually, the questions that often comes to mind related to this particular period

Why did English change from the old to the middle? or

Is Middle English the same as Old English? or what are the differences between old and Middle English?

Contents

To understand the transformation we need to have a little outlook on the history or the background of this age.

In 1066, the Duke of Normandy (located in France) William the Conquerer attacked King Harold of England and defeated him in the Battle Of Hastings.

After the defeat of Harold, William the Conquerer got the throne and started the Anglo-Norman period.

Anglo-Norman is the result of stirring the inhabitance of the germanic tribe’s Angles, Saxons and Jutes who already lived in the British Isles and after 1066, William the Conquerer from Normandy started ruling so the language gets its virtue from these two events.

![As we know English Language , has went through vigorous transformation , down the ages . After the Anglo-Saxon period or the Old English period the most , eventual and significant era was the MIddle English period. Middle English, starts its journey in history of English Literature, after the immigration of the Germanic tribes the Anglo saxon, when the Normans invaded England , in 1066 and continued till the renaissance, some where around 1558. This span of more than 500 years is divided into three parts i) Before Chaucer (1066-1300) ii) Age of Chaucer (1300-1400) iii) Age of Revival (1400-1500) In this article we are going to know about the literature and the literary works, before and after Chaucer . Eventually the questions that often comes to mind related to this particular period Why did English change from old to middle?or Is Middle English the same as Old English? or what are the differences between old and Middle English ? To understand the transformation we need to have little outlook on the history or the background of this age . In 1066 , the Duke of Normandi (located in France) William the Conquerer attacked king Harold of England , and defeated him in the Battle Of Hastings . After the defeat of Harold , William the Conquerer got the throne , and started the Anglo-Norman period . Anglo-Norman is the result of stirring the inhabitance of the , the germanic tribes Angles ,Saxons and Jutes who already lived in the British Isles and after 1066 ,Wiliiam the Conquerer from Normandi started ruling so the language gets its virtue from the these two events. After the battle of Hastings, France became the ruling class in England , which brought the Anglo-French (the official language) at that time. On one side the aristocratic ruling class , spoke French and the middle and lower class, spoke the Old English . This is the time where officially the Middle English was formed , comprised of words taken from both Old English and French. Both of this languages were combined to form the language that we know today as Middle English . As we all know that English is the language which comprises most of the words from influences of either Latin, German and Greek , French also marks its place in shaping the English Language. This is the time when , education started building its path under the Christianity. the Crusade War began and the pope , tried to preach and convert people into Christianity , so the clergymen started educating people with the Romano Latin scripts of Christianity and education also blowed outside the church as people started learning of their own . A very important event in this era was foundation of the two world famous institution, the Cambridge and the Oxford . Due to the Crusades , education was flowing all over England adn London became the Eduacation hub , that is only why if you see the the writers and poets of British History they all belong to London . Literary contexts and literature The term Middle English literature refers to the literature written in the form of the English language known as Middle English, from the 14th century until the 1470s. During this time the Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English became widespread and the printing press regularized the language. Between the 1470s and the middle of the following century there was a transition to early Modern English. In literary terms, the characteristics of the literary works written did not change radically until the effects of the Renaissance and Reformed Christianity became more apparent in the reign of King Henry VIII. There are three main categories of Middle English literature, religious, courtly love, and Arthurian, though much of Geoffrey Chaucer's work stands outside these. Among the many religious works are those in the Katherine Group and the writings of Julian of Norwich and Richard Rolle. What is Middle English poetry? The Age of Chaucer starts the journey for Middle English Poetry , Geoffrey Chaucer " the father of English Literature " called by John Dryden ,because he was the first to write what became generally well-known and recognized poems and stories in the language of the common people of his time - medieval English. He is best known for The Canterbury Tales. Among Chaucer's many other works are The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame, The Legend of Good Women, and Troilus and Criseyde. He is seen as crucial in legitimising the literary use of Middle English when the dominant literary languages in England were still French and Latin. lists of poem that belong to Middle English Period A Adam lay ybounden Alliterative Morte Arthure Amadas Amis and Amiloun Amoryus and Cleopes Anelida and Arcite The Assembly of Gods Athelston The Awntyrs off Arthure B Beves of Hamtoun (poem) Le Bone Florence of Rome The Book of the Duchess C The Canterbury Tales Chanson d'aventure Cleanness Sir Cleges The Complaint of Mars Confessio Amantis Corpus Christi Carol Cursor Mundi D Sir Degrevant E Sir Eglamour of Artois Emaré Erl of Toulouse F The Fall of Princes Flen flyys The Floure and the Leafe Foweles in the frith G Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Generides Sir Gowther H Handlyng Synne I I syng of a mayden Ipomadon The Isle of Ladies Sir Isumbras K Kildare Poems King Alisaunder The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain L Laud Troy Book Sir Launfal Layamon's Brut The Legend of Good Women Libeaus Desconus Lullay, mine liking M Medieval debate poetry Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament Mum and the Sothsegger N NLW MS 733B Piers Plowman Northern Gawain Group Northern Homily Cycle O Octavian (romance) Of Arthour and of Merlin Sir Orfeo Ormulum The Owl and the Nightingale P Parlement of Foules Patience (poem) Pearl (poem) Sir Perceval of Galles Pierce the Ploughman's Crede Piers Plowman Piers Plowman tradition Poem on the Evil Times of Edward II Poema Morale Prick of Conscience Prologue and Tale of Beryn R Richard Coer de Lyon Richard the Redeless Robert of Gloucester (historian) The Rose of Rouen S The Seege of Troye Siege of Thebes (poem) Sir Tristrem Speculum Vitae The Squire of Low Degree St. Erkenwald (poem) Stanzaic Morte Arthur Sumer is icumen in T The Three Dead Kings Torrent of Portyngale Tournament of Tottenham Troilus and Criseyde Troy Book Sir Tryamour W The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle When the Nightingale Sings Wynnere and Wastoure Y Ywain and Gawain 100 most frequent Middle English words al, al be that: although als, also: as, also anon: at once artow: art thou, thou art as: as, as if, like atte: at, at the aventure: chance axe: ask ay: always been: are bet: better beth: are; (imperative) be brenne: burn but, but if: unless can, kan: know, be able canstow: can you, you can cas: happening, chance certes: surely, certainly clepe (n): call clerk: scholar coy: quiet ech: each echo (o) n: each one eek, eke: also er, or: before; formerly everich: every; every one fay, fey: faith forthy: therefore fro: from gan, gonne: began han: have hastow: have you, you have hem: them here: her hight: named, called him lest (list): he wants hir (e): her, their ich: I ilke: same kan: know, know how to; can konne: learn; know how to; can koude: knew; knew how to; could kynde: nature lasse: less le (e) ve: dear lite: little maistow, maystow: may you, you may make: mate, husband, make mo: more moot (e) (n): may, must, ought to; so (also, ever) moot I: as I hope to morewe: morrow, morning mowe: may muche (1): much, many (a) nam: am not namo, namoore, no more nas: was not nat: not nathelees: nevertheless ne: not, nor nere: were not nolde: would not nones, nonys: occasion noon: none, no noot: know not nyce: foolish nys: is not o, oo, on, oon, that oon: one of: of; off pardee: (lit. “by God”), a common oath; certainly prime, pryme: 9 A.M. quod: said rathe: early, soon rede: advise; interpret; read seistow: you say sely: innocent, simple seyde: said seye: say shaltow: you shall Did Shakespeare use Middle English? No. The works of William Shakespeare are written in what is known as Early Modern English. Middle English was used between the late 11th and late 15th centuries. Shakespeare was born in 1564, well after the date of 1470 that is usually given as the end of the era of Middle English. Features of Middle English phonology The following sections should be seen in the context of the above one Writing and Sounds of Old English as it offers a discussion of the main changes between Old and Middle English and elaborates on some of the features of Middle English which are relevant to developments today. LENGTHENING IN OPEN SYLLABLES This is a phonological process which started in the north of England in the 13th century and affected the high vowels /i/ and /u/ in the following century. It is one of the major sound changes of early Middle English and involves lengthening and lowering as seen in the following examples. RETENTION OF MORA THROUGH COMPENSATORY LENGTHENING To understand Open Syllable Lengthening properly one must start with the notion of mora. A mora corresponds metrically to the quality of a short vowel; all long vowels and diphthongs are bimoric in English. The constituents of a syllable correspond to morae in metrics. One can see that in the history of English various cases of compensatory lengthening recognize that with the loss of a consonant its mora is transferred to a preceding vowel, for instance light /lɪxt/ [lɪçt] (-VCC) > /li:t/ (-V:C). SYLLABIC RESTRUCTURING Recall here that a metrical foot (F = foot) refers to those syllables which stand between two stressed (S = strong, i.e. stressed, indicated by a superscript stroke: ˡ) syllables including the first stressed syllable, irrespective of the number of weak, i.e. unstressed (W = weak) syllables after it: ˡHe’s preˡdicting a ˡlandslide ˡvictory. The labels S, ‘strong’, and W, ‘weak’, refer to the relative accentuation of the syllable. With the designations L, ‘light’, and H, ‘heavy’, the reference is to the quantity of the syllable. The correlation between strong and heavy on the one hand and weak and light on the other is in Middle English such that when a syllable is the only one in a foot then it must also be ‘heavy’, hence the lengthening of short stressed vowels after the loss of final /ə/. The entire metrical quantity of the words was retained by Open Syllable Lengthening. VOWELS BEFORE /X/ In West Saxon there were only two recognisable variants for /x/, [h] in initial position, [x] in all other positions, irrespective of the preceding vowel. It was only towards the end of the Old English period that the variant [ç] appears as an allophone after front vowels. In Middle English this led to a diphthong with the mid front vowels /e/ and /e:/. There is an equivalent to the diphthongisation of [e(:)ç] to [eiç] with back vowels. With the latter vowels the allophone was [x] up to early Middle English. During this period a velar glide appears before this sound, [u], the back equivalent to /i/ with [ç]. This merged with the preceding vowel and resulted in a diphthong. THE SHIFT OF /X/ TO /F/ Already by the 14th century a shift is to be found in English which is common in many other languages as well. It is the shift among fricatives from velar to labial place of articulation. In English the shift was unidirectional and represents one of the many reflexes of /-x/ in Modern English (the remaining reflexes are vocalic). Note that there are two main outputs from this shift, one with an original high vowel /ʊ/ (later lowered to /ʌ/) and one with a mid back vowel /ɔ/; occasionally the shift occurred with a mid front vowel, cf. the form dwarf which itself shows later lowering of /e/ to /a/ before /r/. SHORT VOWEL DEVELOPMENTS The development of late Old English /y/ differed in the various dialects. In Kentish the vowel had already unrounded to /ɛ/ in the late 9th century; in the west midlands and in the south-west it was retained in the Middle English period. In the east midlands it was probably unrounded early on (after the 11th century). late OE ME y i North and East Midlands y West Midlands and South ɛ Kent There are many examples for the unrounding in the east midlands. The development in the east applies to those cases where there was no phonetic conditioning. If, however, /y/ came after a labial or in the environment of /ʃ/ or before /dʒ, tʃ, ʃ/ it was retracted to /u/. Western dialects show the retraction already in the 12th century and this is responsible for many of the spellings with u to the present day. In the west midlands and in the south a front vowel was retained longest. The spelling u there stands for /y/ and is not restricted to the environment before /dʒ, tʃ, ʃ/, cf. gult /gylt/ ‘guilt’, kun /kyn/ ‘kin’. For Kentish /ɛ/ is attested. The vowel is the short equivalent zu /e:/ which was already to be found in Kentish instead of West Saxon /y:/. Cf. gelt /gɛlt/ ‘guilt’, ken /kɛn/ ‘kin’. The modern standard shows forms which can be traced to the various dialects. The phonetic possibilities are /ɪ/, /ɛ/ or /ʌ/ (from earlier /ʊ/) and the spelling can be i,e or u. There are many instances of a mixture of spelling from one dialect and pronunciation from another. SPELLING AND PRONUNCIATION busy West Midlands East Midlands bury West Midlands Kent merry Kent Kent shut West Midlands West Midlands pit East Midlands East Midlands Apart from the above developments the short vowels of English have remained remarkably stable throughout the history of the language, for instance Old English cwic, god show the same vowels in Modern English. The two main changes which occur later are (1) /ʊ/ > /ʌ/ after the mid-17th century and (2) an earlier raising of /ɛ/ to /ɪ/ before nasals as in think [θɪk] and English [ɪŋglɪʃ]. Lowering of /e/ to /a/ This is a development which began in the north and spread to the south after about 1400. It is difficult to date this exactly as there is no orthographical indication of the shift. The lowering of /e/ to /a/ explains the present-day pronunciations of many proper names in England such as Derby, Hertfordshire, Berkeley (the name of the philosopher, not that of the Californian city). This shift was very common and in many cases the orthography has been adapted to the pronunciation so that these words cannot be recognised as having originally involved the shift, e.g. dark (from derk), barn (from bern), heart (from herte). The shift affected words irrespective of origin, hence some French loans also have the shift. Note that many instances did not become established and the /er/ (later /ɜ:/) pronunciation was retained. Early Modern English serve /sarv/ > /sɜ:v/ certain /sartɪn/ > /sɜ:tən/ fervent /farvɪnt/ > /fɜ:vɪnt/ In one case this development led to a semantic distinction between two words one with the lowered vowel and one without. The word parson is a form of person with this lowering and came to mean not just any person but an ecclesiastical person and so the two forms continued with separate meanings in the standard. THE LOSS OF FINAL /-ə/ The loss of phonetic substance in words is one of the most remarking developments in the history of English. It is already attested in Old English in the simplification of consonants. Later vowels in unstressed syllables lost their distinctiveness, then a final inflectional nasal was dropped and finally — probably by the 14th century — the remaining shwa, [ə], disappeared as can be seen in the following sequence. drīfan /dri:van/ > /dri:vən/ > /dri:və/ > /dri:v/ (> /draiv/) This phonetic loss always involves unstressed syllables and usually resulted in apocope (loss of endings). There are, however, instances of syncope (medial loss) and procope (initial loss). The latter can be seen quite clearly with the past participles of verbs which originally had a prefix ge- (cf. the similar prefix in German) but which was weakened progressively until it finally disappeared. ge- /jə-/ > /i:/ > /ɪ/ > ø OE gelufod ME yloved NE loved This phonetic reduction had far-reaching consequences for the typology of English which gradually drifted from a synthetic type (Old English, much like German) to a more analytic type in modern times. The language developed means for compensating for the loss in manifestation of grammatical categories chiefly by a more rigid word order and by the increasing functionalisation of prepositions. It is difficult to reconstruct the demise of final /ə/. The reason is quite simply that final -e continued to be written. The only sound proof is offered by a series of spellings in Middle English where the words have a final -e which is not etymologically justified. cōle (OE col) ‘coal’ shīre (OE scīr) ‘county’ The loss of phonetic /-ə/ led to a refunctionalisation of the final written -e. It was henceforth used to indicate that the vowel of the preceding (stressed) syllable was long. This function has survived to the present day, cf. pane, with /ei/ from ME /a:/, and pan, with /æ/ from ME /a/. In cases where final /-l/ is still spoken one must differentiate between those which represent a retention of an inherited /-l/ and those where the /-l/ is pronounced because it was reintroduced into the writing, e.g. ModE fault (< ME faute from French). The situation is slightly different where the present-day English word shows a long low vowel. Here the /-l/ can have disappeared without necessarily having caused a diphthong. calf /ka:f/, half /ha:f/](https://elizabethanenglandlife.com/images/420px-Norman-conquest-1066.svg_-1.png)

On one side the aristocratic ruling class spoke French and the middle and lower class spoke the Old English.

This is the time where officially the Middle English was formed, comprised of words taken from both Old English and French. Both of these languages were combined to form the language that we know today as Middle English.

As we all know that English is the language which comprises most of the words from influences of either Latin, German and Greek, French also marks its place in shaping the English Language.

This is the time when education started building its path under Christianity. the Crusade War began and the pope, tried to preach and convert people into Christianity, so the clergymen started educating people with the Romano Latin scripts of Christianity and education also blew outside the church as people started learning of their own.

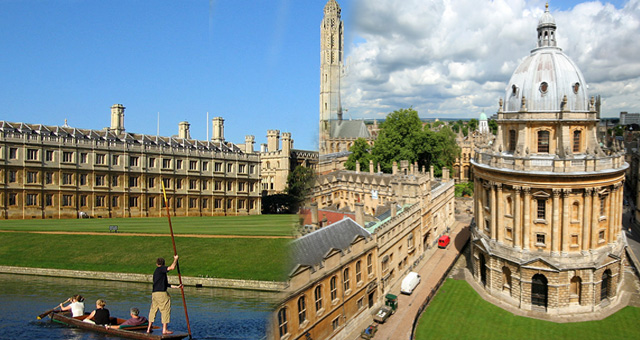

A very important event in this era was the foundation of the two world-famous institutions, the Cambridge and the Oxford.

Due to the Crusades, education was flowing all over England and London became the Education hub, that is only why if you see the writers and poets of British History they all belong to London.

Literary contexts and literature

The term Middle English literature refers to the literature written in the form of the English language known as Middle English, from the 14th century until the 1470s. During this time the Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English became widespread and the printing press regularized the language.

Between the 1470s and the middle of the following century, there was a transition to early Modern English. In literary terms, the characteristics of the literary works written did not change radically until the effects of the Renaissance and Reformed Christianity became more apparent in the reign of King Henry VIII.

There are three main categories of Middle English literature, religious, courtly love, and Arthurian, though much of Geoffrey Chaucer’s work stands outside these. Among the many religious works are those in the Katherine Group and the writings of Julian of Norwich and Richard Rolle.

What is Middle English poetry?

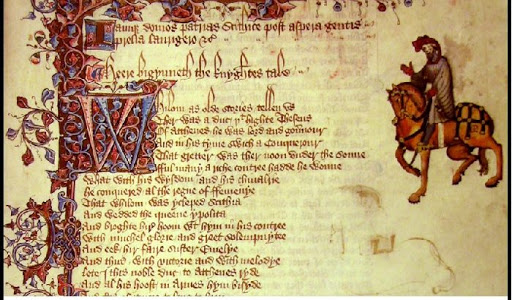

The Age of Chaucer starts the journey for Middle English Poetry, Geoffrey Chaucer ” the father of English Literature ” called by John Dryden, because he was the first to write what became generally well-known and recognized poems and stories in the language of the common people of his time – medieval English.

He is best known for The Canterbury Tales.

Among Chaucer’s many other works is The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame, The Legend of Good Women, and Troilus and Criseyde.

He is seen as crucial in legitimizing the literary use of Middle English when the dominant literary languages in England were still French and Latin.

List of poems that belong to the Middle English Period

A

Adam lay ybounden

Alliterative Morte Arthure

Amadas

Amis and Amiloun

Amoryus and Cleopes

Anelida and Arcite

The Assembly of Gods

Athelston

The Awntyrs off Arthure

B

Beves of Hamtoun (poem)

Le Bone Florence of Rome

The Book of the Duchess

C

The Canterbury Tales

Chanson d’aventure

Cleanness

Sir Cleges

The Complaint of Mars

Confessio Amantis

Corpus Christi Carol

Cursor Mundi

D

Sir Degrevant

E

Sir Eglamour of Artois

Emaré

Erl of Toulouse

F

The Fall of Princes

Flen flyys

The Floure and the Leafe

Foweles in the frith

G

Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Generides

Sir Gowther

H

Handlyng Synne

I

I syng of a mayden

Ipomadon

The Isle of Ladies

Sir Isumbras

K

Kildare Poems

King Alisaunder

The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain

L

Laud Troy Book

Sir Launfal

Layamon’s Brut

The Legend of Good Women

Libeaus Desconus

Lullay, mine liking

M

Medieval debate poetry

Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament

Mum and the Sothsegger

N

NLW MS 733B Piers Plowman

Northern Gawain Group

Northern Homily Cycle

O

Octavian (romance)

Of Arthour and of Merlin

Sir Orfeo

Ormulum

The Owl and the Nightingale

P

Parlement of Foules

Patience (poem)

Pearl (poem)

Sir Perceval of Galles

Pierce the Ploughman’s Crede

Piers Plowman

Piers Plowman tradition

Poem on the Evil Times of Edward II

Poema Morale

Prick of Conscience

Prologue and Tale of Beryn

R

Richard Coer de Lyon

Richard the Redeless

Robert of Gloucester (historian)

The Rose of Rouen

S

The Seege of Troye

Siege of Thebes (poem)

Sir Tristrem

Speculum Vitae

The Squire of Low Degree

St. Erkenwald (poem)

Stanzaic Morte Arthur

Sumer is icumen in

T

The Three Dead Kings

Torrent of Portyngale

Tournament of Tottenham

Troilus and Criseyde

Troy Book

Sir Tryamour

W

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle

When the Nightingale Sings

Wynnere and Wastoure

Y

Ywain and Gawain

Most frequent Middle English words

al, al be that: although

als, also: as, also

anon: at once

artow: art thou, thou art

as: as, as if, like

atte: at, at the

aventure: chance

axe: ask

ay: always

been: are

bet: better

beth: are; (imperative) be

brenne: burn

but, but if: unless

can, kan: know, be able

canstow: can you, you can

cas: happening, chance

certes: surely, certainly

clepe (n): call

clerk: scholar

coy: quiet

ech: each

echo (o) n: each one

eek, eke: also

er, or: before; formerly

everich: every; every one

fay, fey: faith

forthy: therefore

fro: from

gan, gonne: began

han: have

hastow: have you, you have

hem: them

here: her

hight: named, called

him lest (list): he wants

hir (e): her, their

ich: I

ilke: same

kan: know, know how to; can

konne: learn; know how to; can

koude: knew; knew how to; could

kynde: nature

lasse: less

le (e) ve: dear

lite: little

maistow, maystow: may you, you may

make: mate, husband, make

mo: more

moot (e) (n): may, must, ought to; so (also, ever) moot I: as I hope to

morewe: morrow, morning

mowe: may

muche (1): much, many (a)

nam: am not

namo, namoore, no more

nas: was not

nat: not

nathelees: nevertheless

ne: not, nor

nere: were not

nolde: would not

nones, nonys: occasion

noon: none, no

noot: know not

nyce: foolish

nys: is not

o, oo, on, oon, that oon: one

of: of; off

pardee: (lit. “by God”), a common oath; certainly

prime, pryme: 9 A.M.

quod: said

rathe: early, soon

rede: advise; interpret; read

seistow: you say

sely: innocent, simple

seyde: said

seye: say

shaltow: you shall

Did Shakespeare use Middle English?

No. The works of William Shakespeare are written in what is known as Early Modern English. Middle English was used between the late 11th and late 15th centuries. Shakespeare was born in 1564, well after the date of 1470 that is usually given as the end of the era of Middle English.

Features of Middle English phonology

The following sections should be seen in the context of the above one Writing and Sounds of Old English as it offers a discussion of the main changes between Old and Middle English and elaborates on some of the features of Middle English which are relevant to developments today.

LENGTHENING IN OPEN SYLLABLES

This is a phonological process which started in the north of England in the 13th century and affected the high vowels /i/ and /u/ in the following century. It is one of the major sound changes of early Middle English and involves lengthening and lowering as seen in the following examples.

RETENTION OF MORA THROUGH COMPENSATORY LENGTHENING

To understand Open Syllable Lengthening properly one must start with the notion of mora. A mora corresponds metrically to the quality of a short vowel; all long vowels and diphthongs are biometric in English. The constituents of a syllable correspond to morae in metrics.

One can see that in the history of English various cases of compensatory lengthening recognize that with the loss of a consonant its mora is transferred to a preceding vowel, for instance light /lɪxt/ [lɪçt] (-VCC) > /li:t/ (-V:C).

SYLLABIC RESTRUCTURING

Recall here that a metrical foot (F = foot) refers to those syllables which stand between two stressed (S = strong, i.e. stressed, indicated by a superscript stroke: ˡ) syllables including the first stressed syllable, irrespective of the number of weak, i.e. unstressed (W = weak) syllables after it: ˡHe’s preˡdicting a ˡlandslide ˡvictory.

The labels S, ‘strong’, and W, ‘weak’, refer to the relative accentuation of the syllable. With the designations L, ‘light’, and H, ‘heavy’, the reference is to the quantity of the syllable.

The correlation between strong and heavy on the one hand and weak and light on the other is in Middle English such that when a syllable is the only one in a foot then it must also be ‘heavy’, hence the lengthening of short stressed vowels after the loss of final /ə/. The entire metrical quantity of the words was retained by Open Syllable Lengthening.

VOWELS BEFORE

/X/ In West Saxon there were only two recognisable variants for /x/, [h] in initial position, [x] in all other positions, irrespective of the preceding vowel. It was only towards the end of the Old English period that the variant [ç] appears as an allophone after front vowels. In Middle English this led to a diphthong with the mid front vowels /e/ and /e:/.

There is an equivalent to the diphthongisation of [e(:)ç] to [eiç] with back vowels. With the latter vowels the allophone was [x] up to early Middle English. During this period a velar glide appears before this sound, [u], the back equivalent to /i/ with [ç]. This merged with the preceding vowel and resulted in a diphthong.

THE SHIFT OF /X/ TO /F/

Already by the 14th century a shift is to be found in English which is common in many other languages as well. It is the shift among fricatives from velar to labial place of articulation. In English the shift was unidirectional and represents one of the many reflexes of /-x/ in Modern English (the remaining reflexes are vocalic).

Note that there are two main outputs from this shift, one with an original high vowel /ʊ/ (later lowered to /ʌ/) and one with a mid back vowel /ɔ/; occasionally the shift occurred with a mid front vowel, cf. the form dwarf which itself shows later lowering of /e/ to /a/ before /r/.

SHORT VOWEL DEVELOPMENTS

The development of late Old English /y/ differed in the various dialects. In Kentish the vowel had already unrounded to /ɛ/ in the late 9th century; in the west midlands and in the south-west it was retained in the Middle English period. In the east midlands it was probably unrounded early on (after the 11th century).

late OE

ME

y

i North and East Midlands

y West Midlands and South

ɛ Kent

There are many examples for the unrounding in the east midlands.

The development in the east applies to those cases where there was no phonetic conditioning. If, however, /y/ came after a labial or in the environment of /ʃ/ or before /dʒ, tʃ, ʃ/ it was retracted to /u/. Western dialects show the retraction already in the 12th century and this is responsible for many of the spellings with u to the present day.

In the west midlands and in the south a front vowel was retained longest. The spelling u there stands for /y/ and is not restricted to the environment before /dʒ, tʃ, ʃ/, cf. gult /gylt/ ‘guilt’, kun /kyn/ ‘kin’.

For Kentish /ɛ/ is attested. The vowel is the short equivalent zu /e:/ which was already to be found in Kentish instead of West Saxon /y:/. Cf. gelt /gɛlt/ ‘guilt’, ken /kɛn/ ‘kin’.

The modern standard shows forms which can be traced to the various dialects. The phonetic possibilities are /ɪ/, /ɛ/ or /ʌ/ (from earlier /ʊ/) and the spelling can be i,e or u. There are many instances of a mixture of spelling from one dialect and pronunciation from another.

SPELLING AND PRONUNCIATION

busy (West Midlands) (East Midlands)

bury (West Midlands) (Kent)

merry (Kent) (Kent)

shut (West Midlands) ( West Midlands)

West Midlands

spit (East Midlands) ( East Midlands)

Apart from the above developments, the short vowels of English have remained remarkably stable throughout the history of the language, for instance, Old English cwic, god shows the same vowels in Modern English.

The two main changes which occur later are (1) /ʊ/ > /ʌ/ after the mid-17th century and (2) an earlier raising of /ɛ/ to /ɪ/ before nasals as in think [θɪk] and English.

Lowering of /e/ to /a/

This is a development which began in the north and spread to the south after about 1400. It is difficult to date this exactly as there is no orthographical indication of the shift. The lowering of /e/ to /a/ explains the present-day pronunciations of many proper names in England such as Derby, Hertfordshire, Berkeley (the name of the philosopher, not that of the Californian city).

This shift was very common and in many cases, the orthography has been adapted to the pronunciation so that these words cannot be recognized as having originally involved the shift, e.g. dark (from derk), barn (from bern), heart (from herte).

The shift affected words irrespective of origin, hence some French loans also have the shift. Note that many instances did not become established and the /er/ (later /ɜ:/) pronunciation was retained.

Early Modern English

serve /sarv/ > /sɜ:v/

certain /sartɪn/ > /sɜ:tən/

fervent /farvɪnt/ > /fɜ:vɪnt/

In one case this development led to a semantic distinction between two words one with the lowered vowel and one without. The word parson is a form of a person with this lowering and came to mean not just any person but an ecclesiastical person and so the two forms continued with separate meanings in the standard.

THE LOSS OF FINAL

/-ə/ The loss of phonetic substance in words is one of the most remarking developments in the history of English. It is already attested in Old English in the simplification of consonants. Later vowels in unstressed syllables lost their distinctiveness, then a final inflectional nasal was dropped and finally — probably by the 14th century — the remaining shwa, [ə], disappeared as can be seen in the following sequence.

drīfan /dri:van/ > /dri:vən/ > /dri:və/ > /dri:v/ (> /draiv/)

This phonetic loss always involves unstressed syllables and usually resulted in apocope (loss of endings). There are, however, instances of syncope (medial loss) and procope (initial loss).

The latter can be seen quite clearly with the past participles of verbs which originally had a prefix ge- (cf. the similar prefix in German) but which was weakened progressively until it finally disappeared.

ge- /jə-/ > /i:/ > /ɪ/ > ø

OE gelufod ME yloved NE loved

This phonetic reduction had far-reaching consequences for the typology of English which gradually drifted from a synthetic type (Old English, much like German) to a more analytic type in modern times.

The language developed means for compensating for the loss in the manifestation of grammatical categories chiefly by more rigid word order and by the increasing functionalisation of prepositions.

It is difficult to reconstruct the demise of final /ə/. The reason is quite simply that final -e continued to be written. The only soundproof is offered by a series of spellings in Middle English where the words have a finale which is not etymologically justified.

cōle (OE col) ‘coal’

shīre (OE scīr) ‘county’

The loss of phonetic /-ə/ led to a refunctionalisation of the final written -e. It was henceforth used to indicate that the vowel of the preceding (stressed) syllable was long. This function has survived to the present day, cf. pane, with /ei/ from ME /a:/, and pan, with /æ/ from ME /a/.

In cases where final /-l/ is still spoken one must differentiate between those which represent a retention of an inherited /-l/ and those where the /-l/ is pronounced because it was reintroduced into the writing, e.g. ModE fault (< ME faute from French).

The situation is slightly different where the present-day English word shows a long low vowel. Here the /-l/ can have disappeared without necessarily having caused a diphthong.

calf /ka:f/, half /ha:f/